I Hope I Never Mike Again for as Long as I Live

'T his is where I proceed like Morrissey and say something terrible," says Mike Skinner. "That's what ageing musicians are supposed to do, isn't it? They go: 'The thing is, right …'" He grins mischievously: "Just don't make me expect like Eric Clapton, OK?"

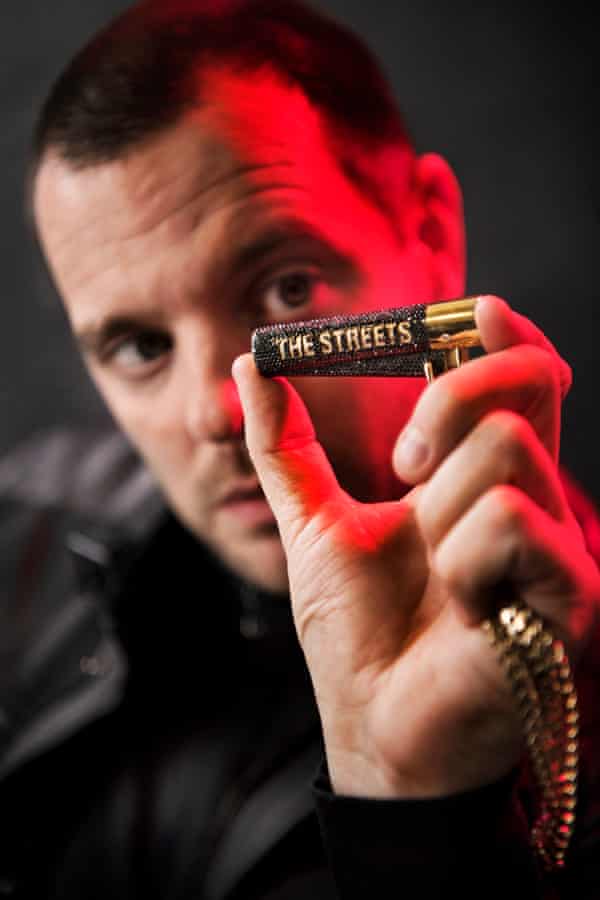

The musician all-time known as the Streets has come prepared for what he has – cheekily – assumed will be a takedown interview. "I don't know whether I need to be cancelled or not. Was Fit But You Know It sexist?" he says, referring to his 2004 single that contained the lyric: "See, I reckon yous're almost an eight or a nine / Maybe even nine-and-a-half in four beers' time." Well, it doesn't await likewise great under a 2022 microscope, I admit. But so, as Skinner points out: "It'southward definitely amend than [the Prodigy'south] Smack My Bowwow Up!"

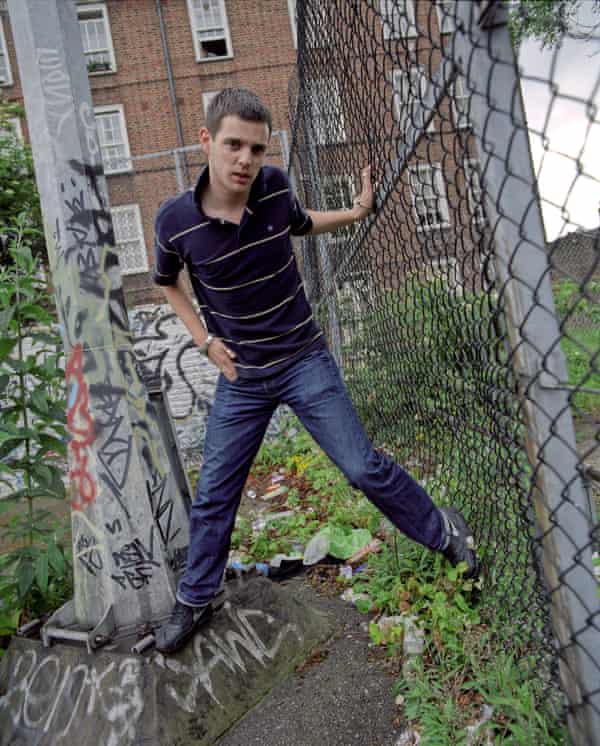

Skinner doesn't need to worry nearly being out of touch, though. He may exist settling into middle historic period at 41, but he's well-nigh to release None of U.s.a. Are Getting Out of This Life Alive, a mixtape full of guest spots from young stars. And while in his 00s heyday the Streets could exist lairy and laddy – Skinner made his proper name rapping about beers, birds and bad takeaways – there was always far more going on with his lyrics. Turn the Page, the opening track of the Streets' 2002 debut Original Pirate Material, referenced the Roman empire, Jimi Hendrix, the Bible, pocketknife criminal offence and Birmingham'due south Bullring – and it was only three minutes long.

Built-in in London, merely raised in Birmingham, Skinner'due south talent was to take UK garage and arrive more relatable to people like him: rather than champagne and velvet VIP ropes, he was conjuring verses nigh Vauxhall Novas and scrambled eggs. Crucially, he plant a way to rap about male fragility in a way that appealed directly to men: revealing their cluelessness around the opposite sexual activity (Don't Mug Yourself), fascination with, and fear of, violence (Geezers Need Excitement) and ultimate self-centredness (Information technology's As well Late). His biggest hit, Dry Your Optics, was a heartfelt exploration of how it feels to be dumped. Even so rather than seeing it as a defining vocal that ripped up the rulebook and made it OK for young men to openly talk about their feelings, Skinner maintains it was just a clumsy attempt to print women. "When yous're a young artist and a male child, you call up: 'At present I'yard gonna write ane for the girls.' And, of class, the girls will never similar it. Because you think: 'Well, girls like something they can sing forth to' and 'Girls similar romance' ... but actually, they kind of similar basslines."

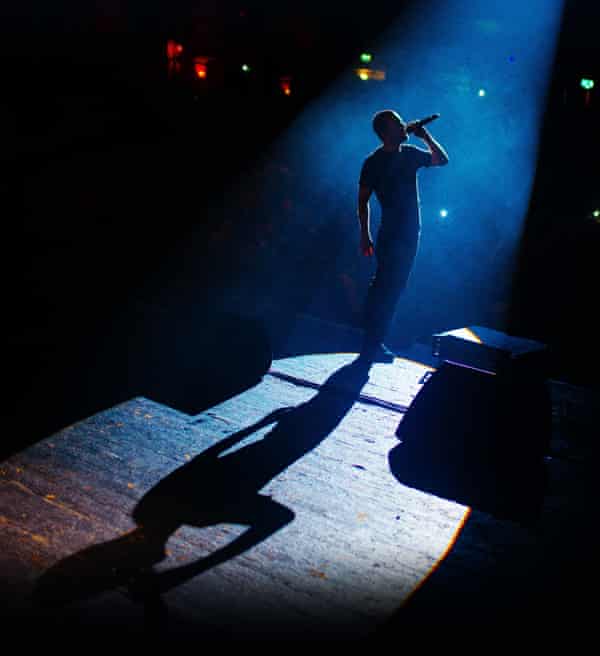

Skinner's intelligence has sometimes seemed equally much of a burden to him as a gift. In the past he has cut a circuitous, self-critical and often frustrated effigy. Skinner wound up the Streets in 2011, albeit he was exhausted with the whole thing. He struggled for subject matter – "You gradually make your life easier and easier until you've got aught left to say" – and success didn't hold with him. At times he could exist petulant – he remembers i bear witness where he got drunk and started mocking the lyrics to It's Too Late. "My A&R human had to say: 'Stop taking the piss, people accept paid to hear something, an emotion.' The matter is, artists want to move on rapidly to the side by side thing. Merely information technology takes fans a long time to go to know and like a song, for it to go a function of their life. If you're not assuasive them to exercise that you're actually only wasting your fourth dimension putting all that effort into the art."

Looking back on that showtime anthology is a strange experience for Skinner because it came so naturally. "People say: 'Oh, they're only xix or 20 and they've made this amazing music,'" he says. "But it'south like ... actually, that's when it's easiest. Y'all've come straight out of the school playground and you're similar: 'That's shit, that's adept, this is what I believe in, go.'"

Original Pirate Material made Skinner famous, but it was the Street's follow up, 2004's A One thousand Don't Come for Free, that sent his fame stratospheric, and his listen into a spin. "I don't by and large have a lot of sympathy for celebrities," he says, "because you can always non walk into the fire. Only if you do, then you lot are admittedly taking a gamble with your mental health. And it'due south a traumatic thing, to be very young and very famous. Not like some traumas, just information technology's … I guess it's a bit similar winning the lottery. It doesn't usually cease well."

Skinner once told an interviewer: "I have to be artistic or I become suicidal or something." Records that grappled with his fame, such equally Prangin' Out, from the Streets' third album, The Hardest Way to Make an Easy Living, contained lyrics about doing "something stupid". Was that really how bad things got?

"I just ever got as far as thinking near information technology," he says. "And thinking nearly information technology is a reason to go to a psychiatrist."

Did he?

"Yeah. I actually saw my psychiatrist only last week. We spent the whole time talking about skiing." He laughs: "I think basically the rule is, if you end upward talking near the psychiatrist, you're probably good."

Effectually the time Skinner'due south career was actually taking off, he lost his father (grief inspired the cute Never Went to Church) after a long illness, which didn't help his emotional struggles. Skinner was the youngest of four siblings, and credits his dad for the wisdom he passed on: "My dad was a lot older – he grew up in the second globe state of war, he literally was in the blitz. He used to listen to Glen Miller ... war joints, know what I mean? But he was incredibly open-minded."

He remembers being dumped as a 14-year-onetime and his dad explaining how things would get easier, but that he would soon take to work out how to wait out for women, too. "He made me see how foreign it must be for a girl to go from being a child to of a sudden forced on to the marketplace. Only someone who has had a previous matrimony, children, literally at the end of their life, could teach fiddling things like that."

Since he first concluded the Streets, Skinner's career has been difficult to untangle. There have been diverse under-the-radar projects such as rock outfit the Dot with the Music'south Rob Harvey, or his slightly rambling Peak Times podcast series with Murkage Dave, the soulful singer with whom he also put on successful, balloon-filled hip-hop and grime Tonga gild nights (sample discussion topics: Müller Rice vs Müller Corner; what if Hitler had Twitter?). In 2017, Skinner brought the Streets back from retirement for a greatest hits tour and a series of collaborative efforts such equally the drum'n'bass order track Take Me Every bit I Am with Chris Lorenzo. Again, it all seemed pretty scattershot, which is how Skinner enjoys working – he likens making his new mixtape to "directing chaos".

Chatting to Skinner can be a bit similar directing chaos, likewise. He is fascinating company, but enquire a question well-nigh one of his songs, for instance, and you're only e'er one stride removed from a tangential discussion most the Cambrian explosion ("Was there really enough time for all these dinosaurs to evolve?") or the way our eyeballs age ("Having watched the Irishman, even the middle-anile Robert de Niro'due south still got erstwhile man eyes. They're more reflective or something.")

"You wonder if nosotros're all part of a magic mushroom experience," he says at i indicate. "Or possibly we're living in a simulation. They do say 50% of all scientific discipline will be disproved ... so really it's a flip of the coin whether annihilation is truthful or not." You sometimes wish yous were downward the pub with him, complimentary to follow him down his countless rabbit holes, rather than marshalling an interview.

Right at present, he appears to have found a project he can finally focus on: a Streets picture show that he has been working on for "donkey's years", but which he hopes will finally kickoff shooting this year. "Information technology'due south a Streets musical, really," he says, shortly before telling me that information technology's not really a Streets musical at all, although information technology does characteristic a soundtrack of Streets music that he wrote about iii years agone. "I love Raymond Chandler and so with the film, it's this idea of a DJ as a sort of cynical or disillusioned private detective," he says. "Basically, imagine if Philip Marlowe was a bass DJ, featuring music from the Streets."

Scriptwriting isn't a new thing for Skinner. A K Don't Come for Free was an ambitious rap opera that wrapped a tale of romance and remorse around the disappearance of £i,000 belonging to the protagonist. To write it, he attended a workshop with the Hollywood screenwriting guru Robert McKee, who taught the likes of Kirk Douglas, Paul Haggis, Joan Rivers and even David Bowie.

That album conspicuously influenced his pic project, merely perhaps not as much as his DJing experience. "I'd spent years and years working on scripts, wondering what I could write about," he says. "Then one dark I was in Manchester, a security guy had but beaten someone up, and I suddenly realised: information technology's very easy to detect stories in nightclubs. It's the heart of the night, people are literally trying to be their worst selves ... even the promoters are! No i'southward there to behave."

Does he still appoint in night-time hedonism himself? "It'due south difficult," he says. "With touring, you lot control everything, so information technology's very piece of cake to practise any you want. If you desire to have smack, play with animals and paint the dressing room every night then that'south fine – you just need to cut a cheque. It'south as well very like shooting fish in a barrel to not exercise that, and discover a routine where information technology'south carrot juice and turmeric lattes every dark rather than directly-up madness. But with DJing, it's non your world y'all're walking into, information technology'due south whatsoever that promoter and that town have created. And so you're hoping it doesn't go left considering information technology's not cool to be xl, in a nightclub, getting off your confront. Just it happens."

Withal, Skinner says he'due south a lot more grownup than he used to be. He has to be, with two kids to look after (Amelia, 10, and George, eight), which must be difficult to residual with the wild nights.

"Well I'1000 definitely going to get Alzheimer's," he laughs. "It's not good for your sleep. But having kids does kind of focus your creativity."

Skinner hasn't stopped championing underground artists. In 2017, his excellent Don't Call It Road Rap documentary for Vice was released, which explored the explosion of the UK rap scene. Filming it, he says he was struck – and slightly embarrassed – by the fact he could be in one of the rougher ends of Kilburn, north London, talking to immature musicians about "prison, illegitimate business, all kinds of goonish stuff", and then take an Uber a few minutes down the road to mix in music and style circles with his wife, Claire Le Marquand, whom he met when she worked at Warner Brothers, his record characterization, and married in 2010.

"I remember I struggled with that for a bit," he says. "But you realise that, actually, y'all can have an incredible sense of purpose that goes with that. Considering I've got so many incredible stories of people changing their lives with rap. And it's a nice affair to see. Because nobody wants a life of criminal offence. It's very difficult work. It'due south much easier to be a musician than a drug dealer."

He says he'south currently trying to run across things from other people's perspectives – be that rightwing financiers, petty criminals or the older generation. "As the so-called metropolitan elite, and I include myself here, I retrieve we owe it to them. Because everybody believes they're the hero in their own story." Reflecting on the current generational divide, he says: "When you're young you recollect old people are a bit stupid. Simply they've washed everything we've done, plus everything the previous generations did, and the one earlier that. I remember onetime people near become Buddhists. They're similar: 'It ain't worth me saying shit then I'm going to just sit hither and chill.'"

You lot tin can imagine Skinner as an old man imparting his wisdom – it's basically what he has been doing through the course of five albums and even so many other projects, an former caput on young shoulders. Back in 2011, when Skinner was exhausted with the Streets, he tried to sum upwardly his career thus far: "For the Streets … overall … I'd say it was a seven out of 10."

It seemed rather harsh considering his impact on British civilization. Today, Skinner appears far less jaded so, before he leaves, I wonder if he has a rosier assessment of his past work.

"I mean ... I still retrieve that'south fair," he says, ever the self-critic. "But I suppose my all-time songs have got to be a 9/10."

He reconsiders this for a second: "And then again, I wouldn't wait anyone to say that their best work wasn't a 9/ten. If yous don't think your best piece of work is a nine then ... you probably need to go and see my psychiatrist."

The first single from the Streets' forthcoming mixtape will be released adjacent month on Island Records

This article was amended on 17 March 2022 because an before version gave Mike Skinner's age as 42. This has been corrected to 41.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/mar/16/mike-skinner-its-not-cool-to-be-40-in-a-nightclub-getting-off-your-face-but-it-happens

0 Response to "I Hope I Never Mike Again for as Long as I Live"

Enregistrer un commentaire